How to Create Your Own Food Forest

Jeremy Puma gives us an expert lesson in permaculture

By: Kasee Bailey

Posted August 01, 2016 on Seattle Magazine.com

Want to grow your own food? Consider creating your own food forest.

Jeremy Puma prefers not to use the word sustainable.

Puma, who is certified in holistic landscape from Bastyr University, is of the opinion that the term simply means sustaining the same things. He prefers generative, meaning a system—like a garden—that produces surplus and promotes sharing.

Puma is talking about food sustainability. He is one of the experts on foraging and introductory permaculture at the Seattle Farm School, an organization that hosts instructive classes (gardening, cooking, arts and crafts) all around West Seattle, including at local businesses or homes. Puma is an especially valuable resource when it comes to food forests, which are purposefully designed spaces that mimic the natural ecology and patterns of healthy ecosystems, like forests.

In food forests, various edibles as well as beneficial flowers and legumes, grow together in support of one another. This, in Puma's words, is a generative system.

Related: A Garden of Eating Blooms on Beacon Hill

Want to grow your own food? Anyone wanting to grow their own food can create a food forest, but it does requires a little thought and planning. Puma walks us through the key steps of building food forest and answers other important questions.

PHOTO CREDIT: Katie Stemp

Creating a food forest: how to begin?

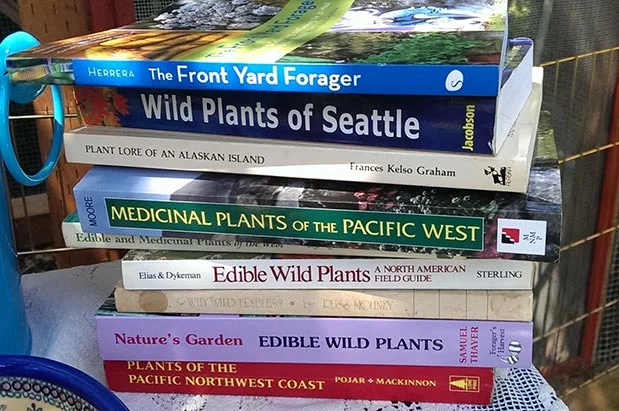

Do your research! There are lots of excellent resources out there for people interested in starting a food forest or forest garden. Start by looking around online, then find some great books on the subject. Consider hiring a professional permaculture landscape designer—the investment could save you time and money. If you're in Seattle, definitely visit the Beacon Hill Food Forest, and consider volunteering.

What are the essential steps for creating your own food forest?

1. After you've done your research, go take a walk in a forest! Observe how all of the species interact with one another, how a forest creates its own mulch and doesn't require watering. Notice the layers in the plant community, from the little guys on the forest floor to the tallest trees, and how they interact with one another. What gets the most light? What doesn't need any light? A walk in the woods is an excellent way to get inspiration for your own food forest, and to get inspired!

2. Make a simple map and assess your site. Is it a backyard or side yard? Is it big enough for what you have in mind? Where does the light fall, and what areas are shadiest? How does the water flow across your site? Have your soil tested—it's free in King County. All of these elements will be useful when you're deciding what to plant. This is where professional assistance can really go a long way.

3. Design a layout and select your plants. Consider that all of the elements in your design should work together as a system, just as in the forest. Forests live in layers: tall trees, short trees, shrubs, herbs, and ground cover. Although you don't have to have all of these elements in your design, keep these layers in mind. Plan for the final product: don't plant a baby apple tree in a space too small for one that's full grown. Don't over-plant, and don't design your plants too close to one another. Plant a variety of edibles, but also consider flowers to attract pollinators and beneficial insects, legumes to fix nitrogen into the soil, plants with taproots to break up compacted earth. Think in terms of "guilds," plant communities that work together for their mutual success.

4. Prepare your site. To make it easy, use a no-till site-preparation method like sheet mulching. Don't forget to call 811 [Washington's Utility Notification Center] before you dig to make sure you're not planting on top of utilities.

5. Find your plants. Go through a local nursery instead of a big box store. The staff will be more knowledgeable and you'll likely find a better, healthier selection. Try to find plants that haven't been treated with neonicotinoids, which are thought to be behind the bee die-off. If you're not sure, ask!

6. Plant your plants! Use compost, then cover the soil around them with a good layer of mulch.

7. Figure out a maintenance schedule based on your plants' needs. This is especially important when your food forest is getting established. Eventually, if you've designed well, you'll need to water less as the food forest adjusts to the climate. The same holds for fertilizer; compost should do at first, but eventually, if you've designed well, the plants will increase soil fertility on their own, and the leaves from your trees will provide a source for mulch.

8. Be patient, especially with your trees! Most fruit and nut trees take years to produce, but once they start fruiting, you'll be able to enjoy the 'fruits' of your labors!

What else can a person do to eat more sustainably?

Grow food and share it! Even if you just plant some lettuce in a window box, the act of growing wholesome fruits and vegetables is, in my opinion, the best gateway to generative living.

Tell us a little about your project with Urban Homestead Foundation. Why is this important?

I'm assisting primarily as a permaculture consultant. The Urban Homestead Foundation will be a groundbreaking way to introduce generative living to the Seattle community. Having a functioning food forest will illustrate that it's possible to grow lots of food in an urban setting by working with natural patterns instead of against them.

The Seattle Farm School has many resources, including classes and a seed-lending library, for those interested in learning more about food sustainability and green gardening techniques.

CATEGORIES: